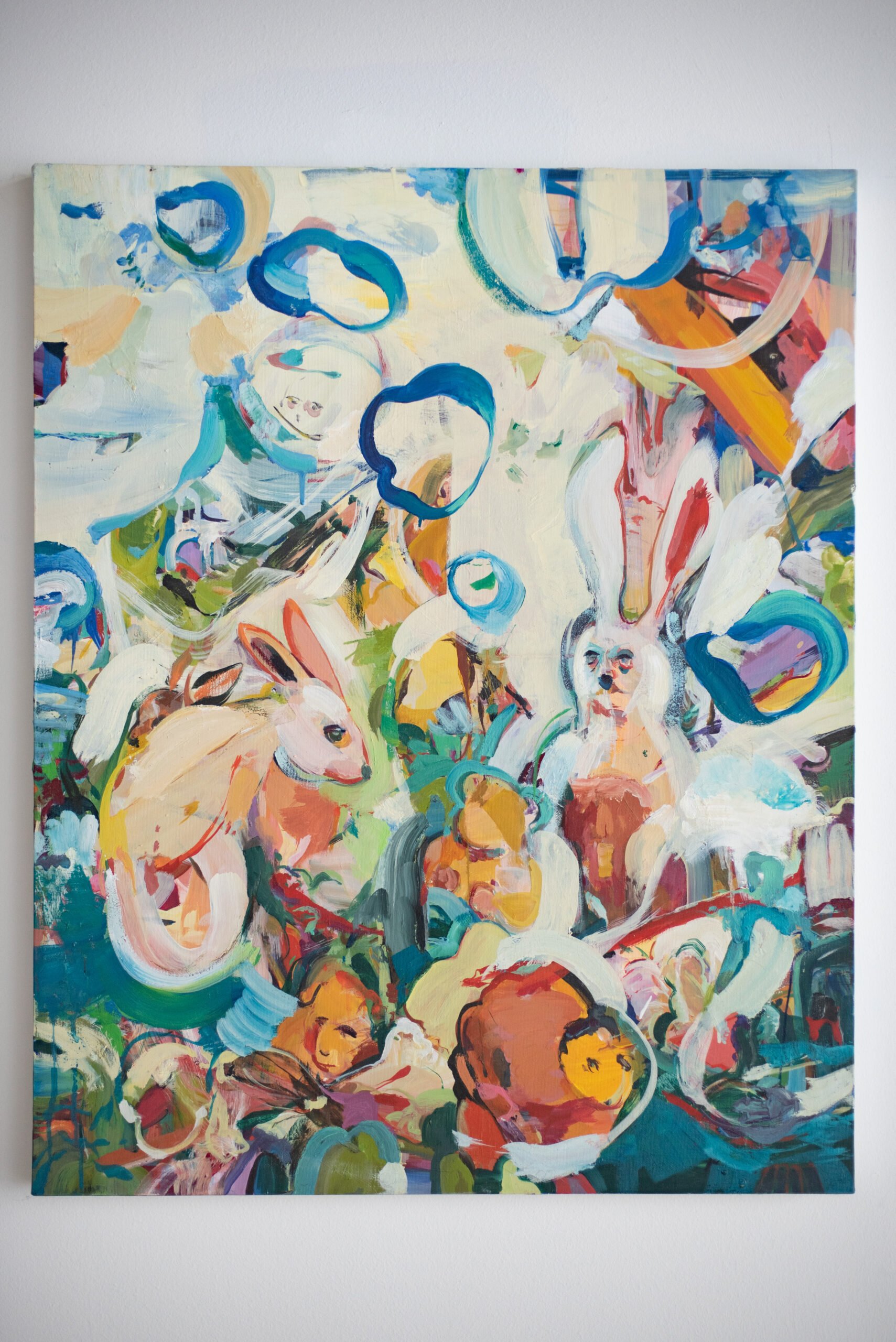

When art explores the vastness of the human condition, it is often the story and intention behind the work that support a piece’s success. Artist Eric Uhlir shares strong perspectives within one canvas when it comes to this stance. The Washington D.C. artist conveys his thoughts on humanity with such depth that it triggers an inner exploration of life, environment, history, and human action and interaction.

He explains, “The world a lot of my paintings inhabit is a reflection of our own. Human beings are incredibly bad at recognizing change over time, especially when it comes to our impact on the natural world. Growing up in LA, I was always fascinated by the city's sprawl, especially out toward the desert. It felt like people wanted to create their own little Arcadias, with these water attentive pools and lawns spreading as far as the eye could see. ”

An expandable technique

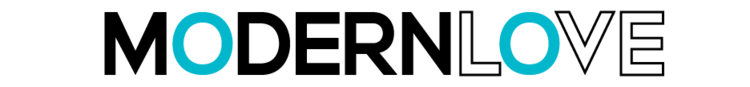

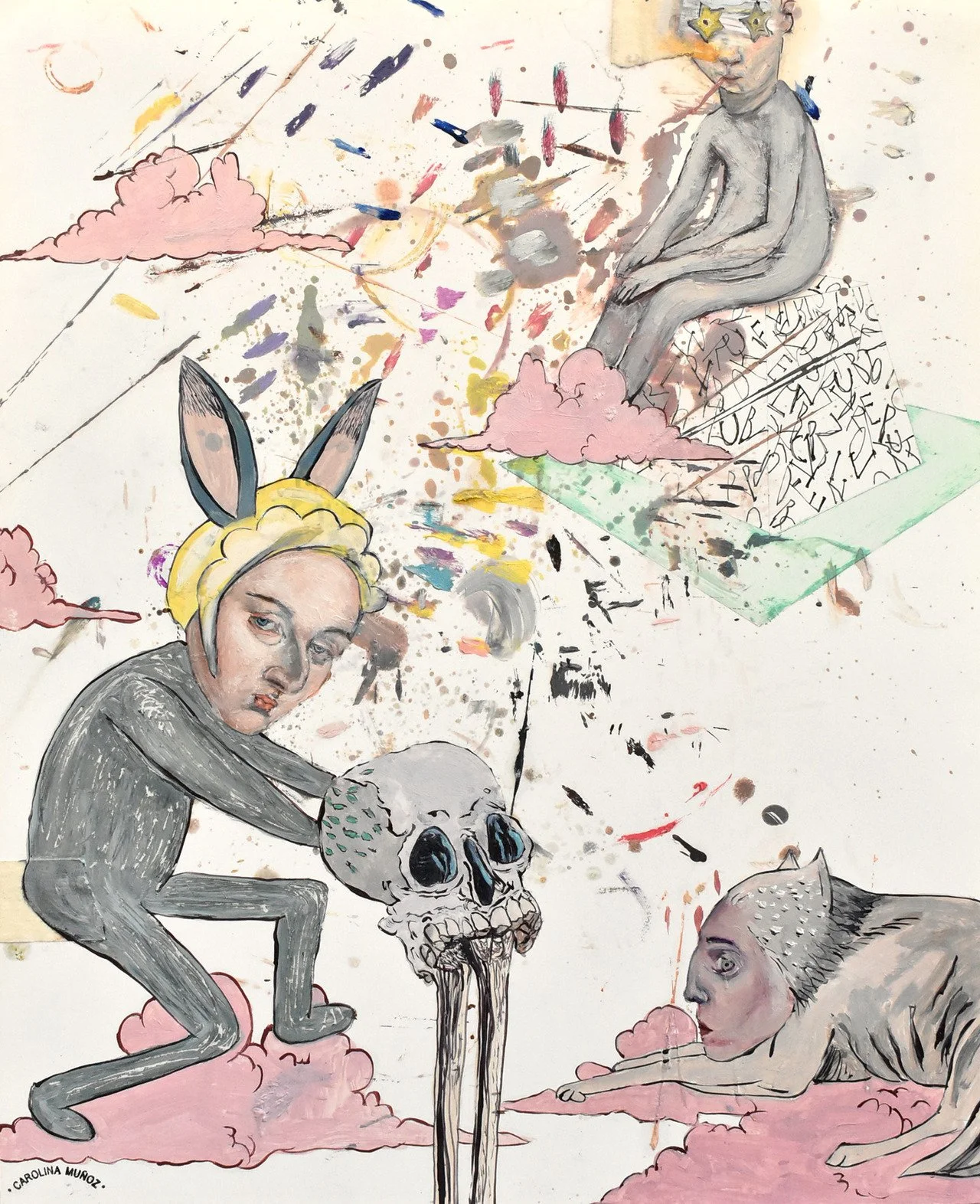

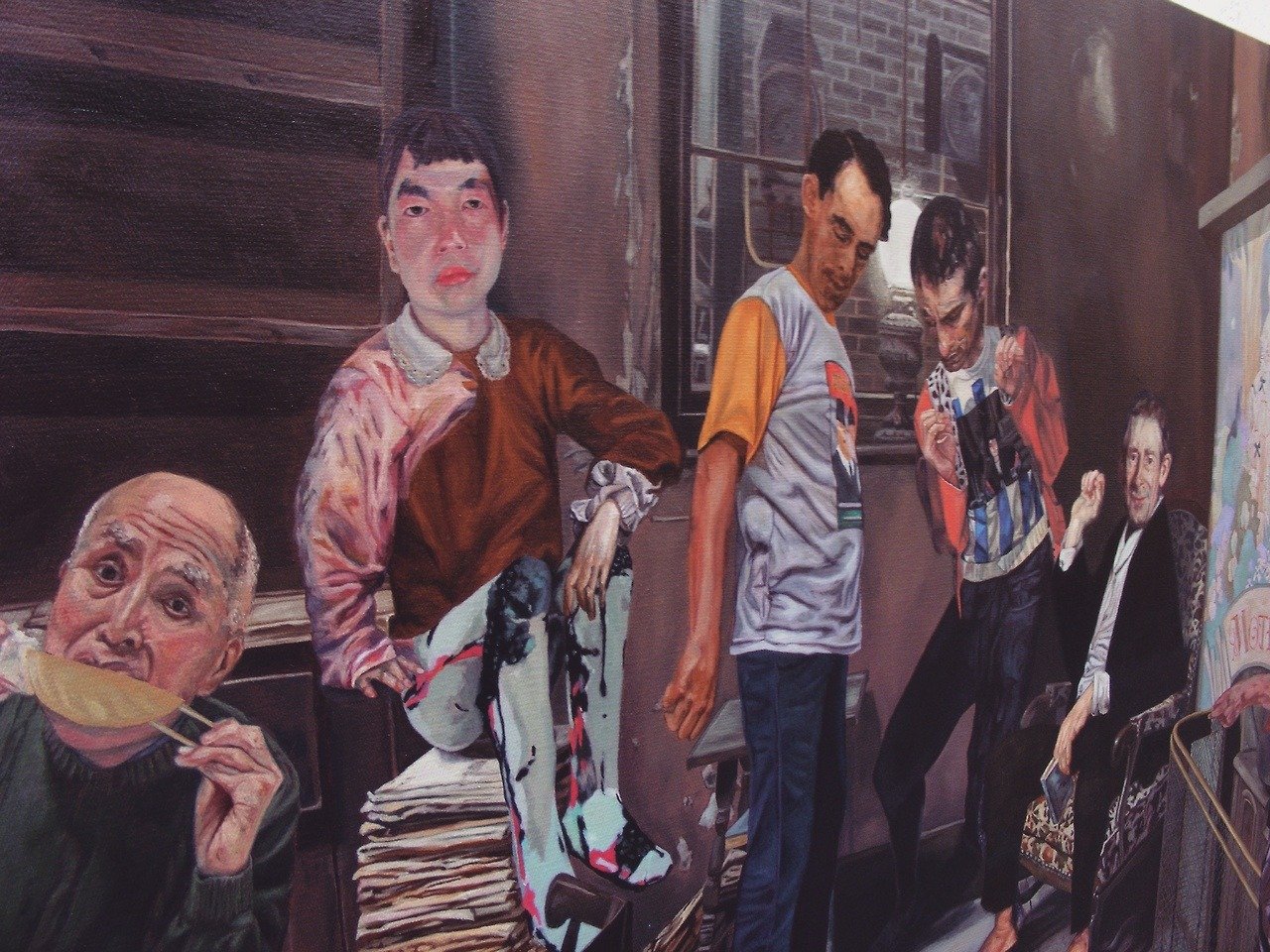

Uhlir’s work captivates through bold colors and movement. There is a dance between both techniques that almost distracts you from observing anything else much further, which is a good thing. It’s almost mesmerizing because this movement tends to cover the entire canvas in a swift manner. Even though there is a great amount of density underneath because of his technique, it is the movement that provides that hypnotic effect through seemingly repetitious curves that open up an entire landscape little by little, making it more intriguing.

He shares:

“I think the palette is entirely due to my childhood in 1980s Los Angeles. The mix of pop culture, advertising, and the California sun imprinted a kind of high-key, full saturation view of the world. The mark-making and energy in each canvas are like a reward for the act of looking. The work I'm making now is very reference-driven, but the actual act of making each painting is highly spontaneous and intuitive. My inner vision is a constant conversation with both external references and the constant experimental studies I make.”

The work isn’t purely figurative, it plays with abstraction. It uses elements like almost abstract figures, transformative forms, gestural strokes, and infinite color blending for each shape represented. Uhlir’s work collectively achieves a magnified effect that persuades you to come face to face with what the painting may be saying to you at that moment. The vibrancy of color also captures what it is like to feel alive during specific moments. Each instance portrayed seems as important as the next. It is because, in Uhlir’s work, these moments are presented in a laser-focused manner through color and view, which then leads to the unraveling of deeper emotions and thoughts for the viewer.

He explains:

“Works on paper, water-based media, and drawings all float around the studio and settle into my subconscious, but the process is very much about the physical muscle memory learned from making marks. It's all very active and purposeful, I don't leave a lot of things hanging around as pure decoration in the paintings. My hope is to give the viewer so much visual information that they are compelled to come back to the work over and over to explore each mark and passage in the painting. I think this active, multi-session commitment to viewing is vital, and it's something we lose in the digital world. It's actually why I don't really make digital work, I want to give you an antidote for all the screens you have to stare at every day.”

On human vision

The way Uhlir uses the canvas has a strong sense of freedom, which stems from intuitive vision and skill. The need to fill up the entire space says something about the way he’s presenting the work to us. The space where his narrative exists feels big and all-encompassing within that frame, regardless of canvas size. You can find people, animals, nature, and scenarios that engulf everything depicted. When you look deeper, you see living beings portrayed through time and space so you can appreciate the complexities of our existence throughout history, and how far we’ve come from certain aspects or not.

This vision also showcases his view of life through a sense of energy and force, and perhaps that is where the movement comes into play. He is showing us that these living beings have their own force, their own agenda, and actions, and how they act upon these passions is up to each and every one of them. Yet the result of these forces affects the other beings, things, or places, which they encounter. Like the phrase, “every action has a reaction,” that is a fraction of the wholeness you encounter in Uhlir’s work, where this sentiment flows beautifully.

He states:

“Art history forms the core references on which I build these almost history painting-esque tableaus. The world is kinetic and abstracted because that's much how we experience our own world, right? More recent works, like "Unity and Division" based on Benjamin West's "Death of General Wolfe", take these structures and examine our own history through the lens of American art history, especially from the colonial era. Remixing paintings by West and others, like John Trumbull, helps me explore how our own experience intersects with these origin myths. It's why so many of the nature works involve references to painters like Gericault, Delacroix, and even Michelangelo. Despite hundreds of years of artists making work about the world, we still seem unable to adequately address systemic racism, environmental disaster, and conflict. Why is that? Do we take all of these images for granted? Can remixing and recontextualizing those original marks through my own lens render something meaningful? These are a lot of the questions I'm investigating through my main body of work.”

Concluding musings

Uhlir has a way of constructing complex narratives through his paintings so that they come alive, metaphorically speaking. They have so much to say when it comes to our reality and our humanistic way of acting. It is through the artwork that we face ourselves as humans, not just in the contemporary reality but from a lineage of humans who since the beginning of time have brought joyful moments into existence just as much as tragic ones. His work shows the human factor range so that we know who we are, where we come from, and taking all that into consideration, maybe we can figure out where we’re going individually and collectively. All while honoring the good and acknowledging the bad and learning from it all. While remembering that it is still magnificent to be alive and to explore existence in the best way possible. The artworks are a representation of our own humanity in a fantastical form. By stepping back we get a glimpse of how our actions and reactions can create waves of emotion, action, and change, and that is a power we shouldn’t ignore.

For more on Eric’s work, please visit his website.

Today’s poem aligns with the theme of human complexity, a concept found in Eric’s work:

The Fascination of What’s Difficult

The fascination of what's difficult

Has dried the sap out of my veins, and rent

Spontaneous joy and natural content

Out of my heart. There's something ails our colt

That must, as if it had not holy blood

Nor on Olympus leaped from cloud to cloud,

Shiver under the lash, strain, sweat and jolt

As though it dragged road metal. My curse on plays

That have to be set up in fifty ways,

On the day's war with every knave and dolt,

Theatre business, management of men.

I swear before the dawn comes round again

I'll find the stable and pull out the bolt.